World Social Protection Report 2024–2026

Universal social protection for climate action and a just transition

Chapter 1. Contending with life-cycle and climate risks: The compelling case for universal social protection

Key messages

-

The climate crisis poses a major threat to humanity and undermines the prospect of a liveable planet and the stability of entire societies. Urgent mitigation and adaptation measures must be taken to slow down the rate of warming and address the impacts on people in a way that reduces poverty and inequality, and promotes decent work and social inclusion. In other words, it requires a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all.

-

Universal social protection is a pivotal policy lever to prevent and address the adverse consequences of the climate crisis and enable a just transition. Decisive policy action is required to reinforce and extend social protection systems and adapt them to new realities.

-

Social protection policies can facilitate structural transformations that are necessary to support climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts. It fosters innovation and productive risk-taking. This dynamism enables workers and enterprises to transition towards more sustainable sectors and resilient modes of production. It thereby enables societies to seize the opportunities that a greener economy will afford.

-

Social protection reduces vulnerability and increases the resilience of people, economies and societies by providing a systematic policy response to mutually reinforcing life-cycle risks and climate-related risks. Thus, it must be a key component of adaptation strategies and part of the solution for addressing climate-related loss and damage.

-

Yet, a just transition is held back by persistent gaps in social protection coverage, adequacy and financing, which also hinder the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Investing in social protection systems is indispensable for a successful just transition. The design and implementation of social protection policies can be more effective, equitable and sustainable when it is achieved through social dialogue.

-

Social protection must currently contend with several interconnected global challenges – migration, ageing, informality, digitalization, fragility and structural inequality. However, this report focuses on the overarching danger we face: the triple planetary crisis of climate change, pollution and biodiversity loss. This triple crisis merits special attention as it poses an existential threat and compounds all other macro challenges.

-

The case for strengthening social protection systems is as compelling as it is urgent. Without universal protection systems, the climate crisis and the just transition will exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and inequalities, when precisely the opposite is needed. Moreover, for ambitious mitigation and environmental policies to be feasible, social protection will be needed to garner public support. Human rights instruments and international social security standards provide essential guidance for building universal social protection systems capable of responding to these challenges and realizing the human right to social security for all.

.1.1 The challenge: Ensuring social protection to address the climate crisis and facilitate a just transition

As the world grapples with the climate crisis, there is increasing attention on the role that social protection can play in supporting climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts and enabling a just transition (see box 1.1). This requires strengthening social protection systems, so that they can effectively deliver a twofold objective: protecting people against ordinary life-cycle risks and supporting action to address the unfolding climate crisis and facilitate a move towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies (see box 1.2). Thus, this report examines the current state of social protection worldwide, discusses challenges and opportunities, and provides concrete policy orientations.

Climate change is undoubtedly the most significant challenge faced by humanity (IPCC 2023b). The world is already 1.1°C warmer compared to pre-industrial levels and even if global warming is limited to 1.5–2°C, the climate crisis is already wreaking havoc and causing unavoidable changes in weather patterns. If warming exceeds 2°C, the world is at risk of slipping towards dangerous “tipping points” (Lenton et al. 2023; UN 2021). Halting global heating requires successful mitigation policy to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions and protect natural greenhouse gas sinks1 in a rapid, yet orderly, just and equitable manner. This also includes policies to encourage more sustainable land use and farming practices, the conservation of biodiversity and other natural resources, as well as a transition towards circular economies.

Climate and environmental change are quickly becoming the largest threats to poverty reduction, decent work, sustainable development and social justice (ILO 2023c). There is growing evidence showing already observed and projected adverse impacts of extreme events and slow-onset changes on human health, employment and livelihoods, labour productivity, displacement and poverty eradication (IPCC 2023a; ILO 2023c; Dang, Hallegatte and Trinh 2024; Hallegatte et al. 2016). Urgent measures need to be put in place to adapt to the new reality and manage its adverse impacts and prevent a vicious cycle of rising vulnerability and deteriorating resilience.

The paradox and injustice of the climate crisis make an equitable response all the more urgent. This is because the most vulnerable populations who have contributed the least to global emissions live in regions most susceptible to the climate crisis. Yet they have the fewest resources to cope with and adapt to the increasingly frequent and intense extreme weather events and slow-onset changes (FAO 2024; Hickel 2020). Children, women, persons with disabilities and older groups are especially vulnerable to its impacts (UNICEF 2021b; UN Women 2023). Furthermore, climate hazards increase poverty among those already experiencing poverty and threaten to push the near-poor into poverty (Hallegatte et al. 2016). It is estimated that, by 2030, without policy action, the climate crisis could result in an additional 132 million people living in extreme poverty, and millions more people living in poverty if measured on the basis of a higher poverty line (World Bank 2020, 12; Jafino et al. 2020). Overcoming these challenges will require an integrated policy response, which must include social protection (IPCC 2023b, 29; ILO 2023c).

Efforts to mitigate global heating and adapt to a changing climate and environment are urgent and have the potential to result in more resilient and inclusive economic growth, and sustainable development (ILO 2023c). However, such positive socio-economic outcomes are far from guaranteed. In fact, climate change mitigation and adaptation policies risk further exacerbating existing inequalities and vulnerabilities unless they are implemented in a way that reinforces equality and inclusivity. For instance, some mitigation or other environmental policies may have adverse impacts on employment, income or prices, and it is increasingly recognized that climate change adaptation requires policies that address structural inequalities and the root causes of vulnerability (UNEP 2022).

Box 1.1 Key climate change terminology

|

Climate action is a concept captured by SDG 13 which calls for urgent comprehensive and collective action to combat climate change and its impact on the planet and its inhabitants. It relates to the action needed to implement the Paris Agreement, and encompasses all mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage responses. Climate change mitigation refers to actions that reduce the rate of climate change. Mitigation policies do this by preventing or reducing emissions (for example, keeping fossil fuels in the ground) or enhancing and protecting the sinks of greenhouse gases that reduce their presence in the atmosphere (for example, forests, soils and oceans). Climate change adaptation refers to the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate change and its effects in order to moderate harm or exploit beneficial opportunities. This includes actions that help reduce vulnerability to weather extremes and natural disasters, rising sea levels, biodiversity loss, or food and water insecurity. Loss and damage refers to the unavoidable impacts of climate change that occur despite, or in the absence of, mitigation and adaptation. Economic loss and damage relates to items that can be monetized relatively easily, such as income, assets and infrastructure. Non-economic loss and damage covers matters such as health, cultural heritage, biodiversity and displacement. Just transition involves maximizing the social and economic opportunities of climate action, while minimizing and carefully managing any negative impacts. A just transition requires effective social dialogue among all groups impacted, and respect for fundamental labour principles and rights. |

Source: Adapted from IPCC (2023b), UNDP (2023b) and ILO (2021b; 2015; 2023b).

Box 1.2 Key social protection terminology

|

Social protection, or social security, is a fundamental human right, not a charity, and an essential instrument to reduce vulnerability and promote people’s rights and dignity. Social protection guarantees access to healthcare and income security over a person’s life course through the provision of benefits in cash or in kind – particularly in relation to sickness, maternity, disability, unemployment, old age or loss of an income earner – and support for families with children, among other needs. Human rights instruments and international social security standards guide social protection policies and their implementation (see box 1.3). Social protection systems (also referred to as social security systems, welfare states or similar terms) encompass the full range of social protection benefits and services provided through different mechanisms including social insurance, universal/categorical schemes and social assistance, and are coordinated with active labour market policies, health, education and care systems, among others. Universal social protection refers to social protection systems that ensure everyone has access to comprehensive, adequate and sustainable protection over their life course, and can access benefits when needed. This was reaffirmed by governments, employers and workers at the 109th Session of the International Labour Conference in 2021 (ILO 2021m) and supported by the Global Partnership for Universal Social Protection (USP2030 2019). As a rights-based approach, this is distinct from the concept of a “social safety net” that provides minimal levels of support targeted at a small number of people identified as poor. This system is without legal guarantees and is often experienced as inadequate, stigmatizing and difficult to access. A social protection floor is a fundamental element of a national social protection system, which guarantees universal access to at least essential healthcare and basic income security for everyone throughout their lives (see box 1.3). |

Note: For a full glossary, see Annex 1.

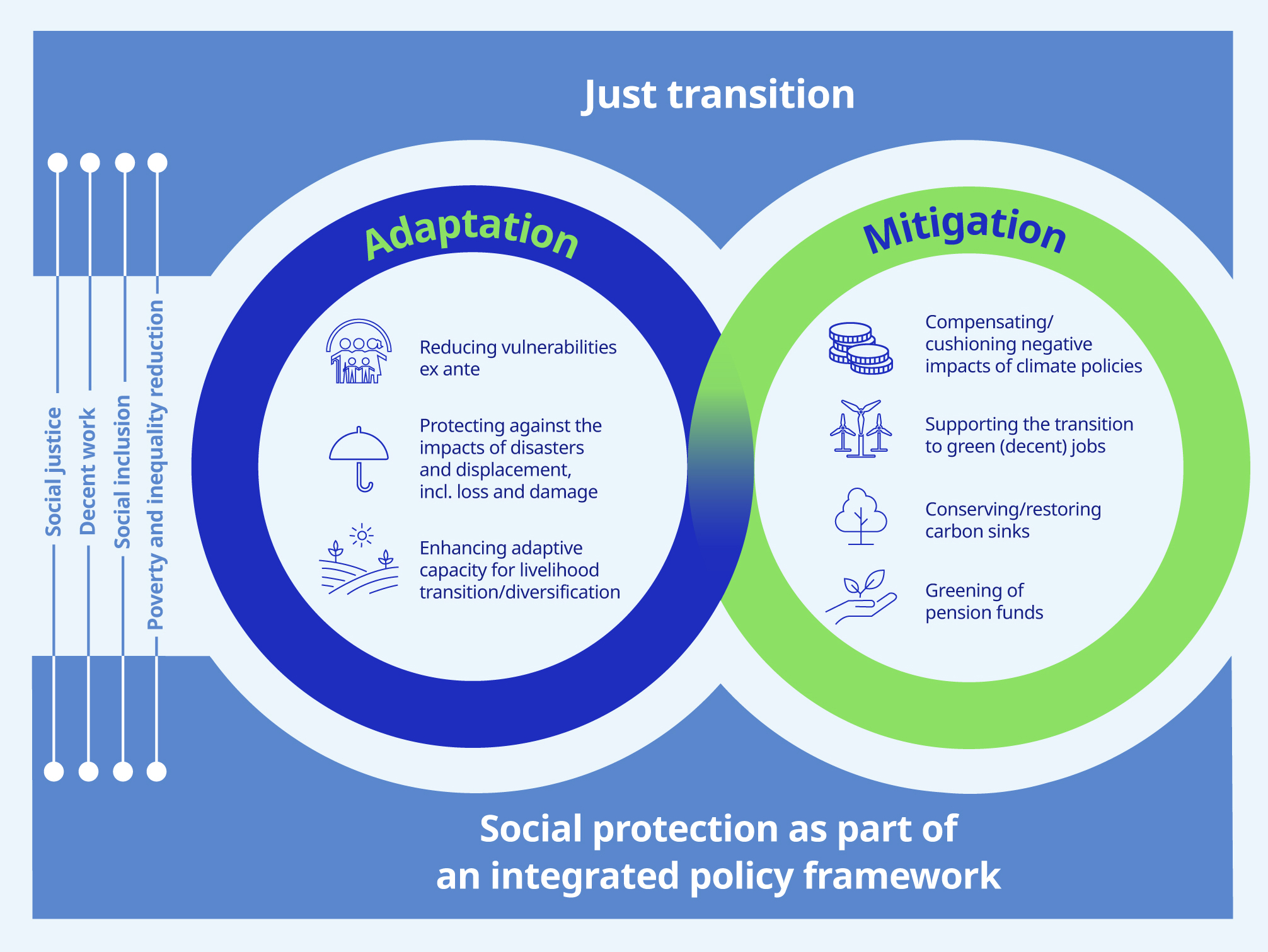

The world needs to rapidly undergo a just transition to environmentally sustainable economies and societies in a way that reduces and prevents poverty and inequalities, promotes decent work and social inclusion and leaves no one behind (ILO 2015c; 2023c; 2023q). While the concept of just transition is often associated with supporting workers in the energy sector affected by climate change mitigation and decarbonization policies – which remains applicable – countries at different levels of development face distinct challenges and priorities with regard to addressing climate and environmental change. Thus, a just transition is relevant to all sectors of the economy (for example, energy, agriculture and forestry, industry, transport, waste and recycling) and all types of workers. Furthermore, mitigation and adaptation efforts, and those addressing loss and damage, must be implemented in such a way that they are equitable for all population groups (figure 1.1). Ultimately, the just transition framework is based on recognizing the need to address not only climate change, but the triple planetary crisis of climate change, pollution and biodiversity loss (ILO 2015c; 2023b).

Figure 1.1 The role of social protection in supporting climate change adaptation and mitigation for a just transition

.1.2 The role of social protection in inclusive climate action and a just transition

To address the aforementioned challenges, building universal, adequate, comprehensive, sustainable and adaptive social protection systems is indispensable for at least three reasons:

-

Strengthening social protection is an important climate change adaptation strategy, especially in countries where social protection coverage is still low. Social protection reduces people’s vulnerability to climate change by providing income security and effective access to healthcare, thus preventing and reducing poverty in the first place, and enabling people to be more resilient. Social protection benefits and services can help individuals, households and societies affected by extreme weather or slow-onset events to cope with and adapt to changing conditions. In coordination with disaster risk management and humanitarian responses, social protection systems can be leveraged to further support people affected by loss and damage, including in the context of forced displacement. Integrated social protection, employment and climate change adaptation policies can enable long-term adaptation and transformation of livelihoods, making them more resilient to the impacts of climate change (Costella et al. 2023; UN 2021).

-

While climate change mitigation and environmental policies are necessary to safeguard the future for all, some policies will inevitably have unintended negative impacts on workers, enterprises and the wider society. Social protection can support those who are adversely affected, including those whose livelihoods are tied to unsustainable practices, and those affected by rising energy or food prices. It can also enable them to seize the opportunities these policies may afford, either by guaranteeing income security to workers who need to reskill and adjust to emerging employment opportunities, or by providing access to healthcare for all. Lastly, social protection can support rural populations in transitioning to more sustainable livelihoods. For such a dynamic to work, it is important to involve the social partners and other stakeholders in the design and implementation of the measures. Ensuring that the new jobs created in the green economy will have decent working conditions and social protection is one of the core elements of a just transition.

-

Social protection is essential in addressing inequalities and inequities, both within and between countries, which is key for reducing vulnerability and enhancing resilience. As a key mechanism of risk sharing and solidarity, social protection systems are indispensable for addressing inequalities, by providing protection and support especially to those who are most vulnerable and least responsible for greenhouse gas emissions and the overuse of natural resources (FAO 2024; Hickel 2020). International support to countries with insufficient fiscal capacities to build financially sustainable national social protection systems, including through loss and damage mechanisms, would make an essential contribution to greater social justice.

If social protection systems are to play this essential enabling role in addressing climate change, they need to provide adequate protection throughout people’s lives.

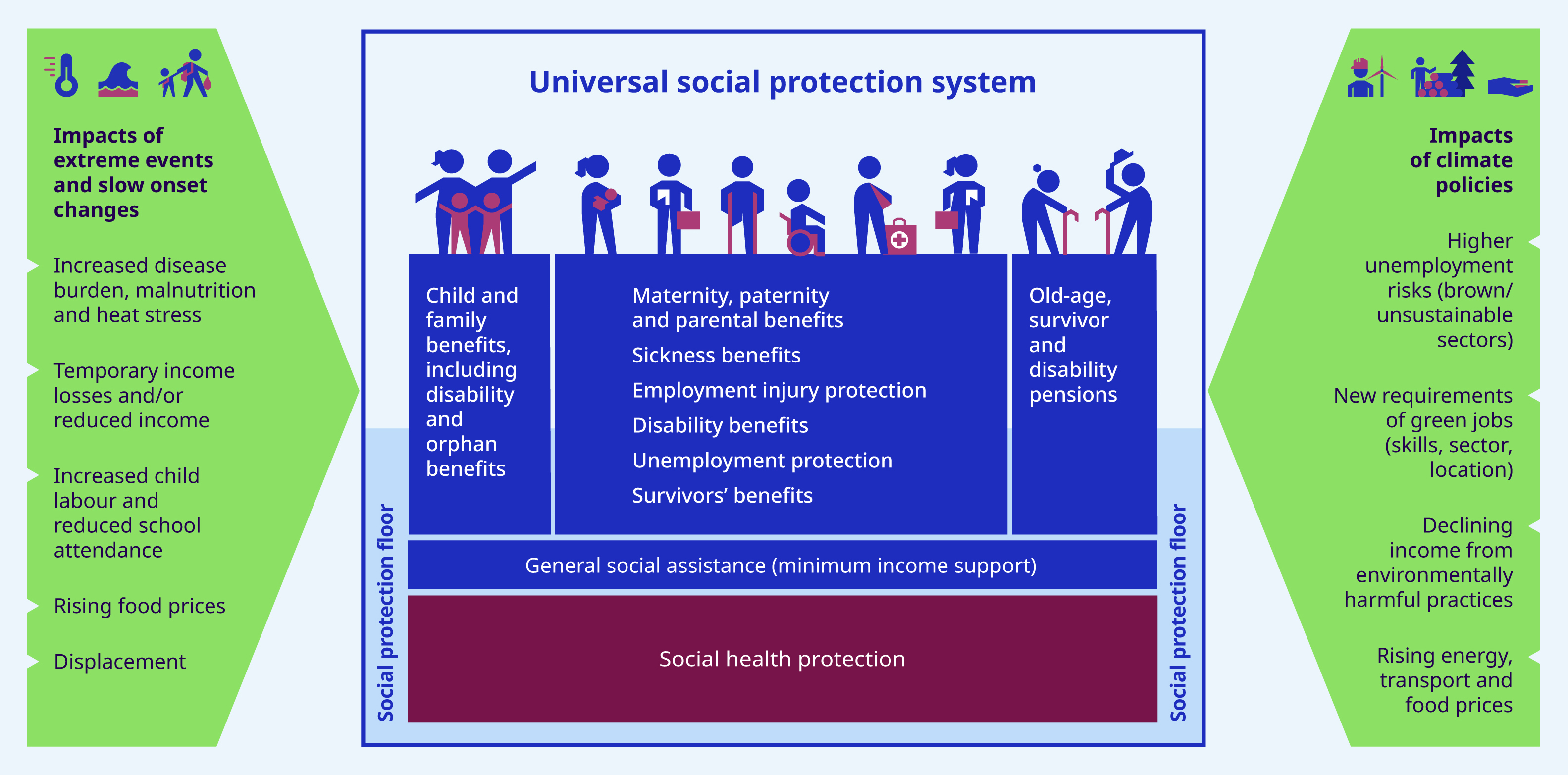

Addressing life-cycle risks is particularly important at critical life phases, when vulnerability and poverty risks are acute, to support life and work transitions. This can be during early childhood, transitions from school to work, the formation of a family, periods of ill health, unemployment, disability and old age. Challenges related to climate change may significantly magnify life cycle risks. For example, people may face greater and different health challenges because of heat stress, pollution or disasters, and they may be at higher risk of job loss or otherwise reduced income. Alternatively, they may face a higher poverty risk due to rising energy and food prices (see figure 1.2). In parallel to climate-related risks, people are facing multiple transformations, whether due to population ageing, migration, digitalization or technological progress, which can have adverse short-and long-term effects that not only undermine their welfare and dignity, but also weaken an already fragile social contract.

Social protection systems enable people to successfully navigate life-cycle and climate risks and multiple transformations. They do this by guaranteeing access to healthcare and income security, thereby enabling people to adapt to change in a way that protects their rights and dignity. Rather than merely containing the downside effects of transformations and crises, social protection can enable people and societies to take advantage of the opportunities inherent in these changes by addressing inequalities and reducing poverty and vulnerability. This allows people and societies to reap the benefits of climate change mitigation and adaptation policies (see figure 1.1).

The importance of social protection is recognized by decisions adopted at international climate negotiations, including most recently at COP28 (UN 2023e; 2023a; 2023b), for enabling climate-resilient development (IPCC 2023b). As an essential contribution to climate justice and a just transition, social protection should be recognized as part of nationally determined contributions, national adaptation plans and climate investment plans.

Figure 1.2 Illustration of the role of social protection in addressing life-cycle and climate risks

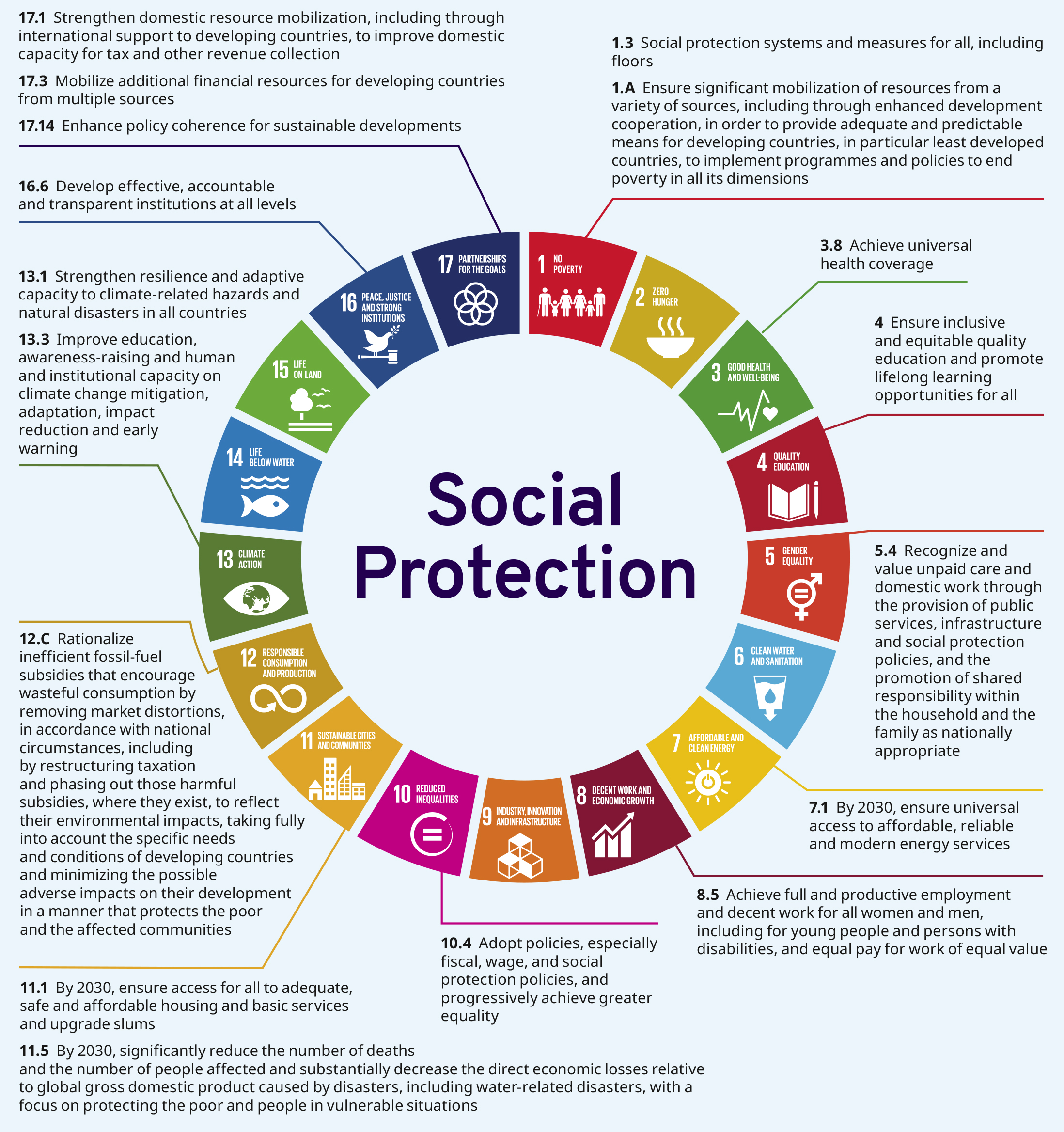

Figure 1.3 Contribution of social protection to the 2030 Agenda

Investing in universal social protection systems allows societies to manage the urgently needed transition in a socially just way by pursuing human-centred policies. This enables people and societies to adjust to ongoing and emerging transformations by directly or indirectly contributing to several SDGs, across the social, economic and environmental dimensions of the 2030 Agenda (figure 1.3).

Not just any investment in social protection will do. What is required is sustainable and equitable investment in rights-based social protection systems that leave no one behind (see box 1.3).

Box 1.3 The international normative framework for building social protection systems, including floors

|

International social security standards, which complement human rights instruments, provide a comprehensive international normative framework for the realization of the human right to social security. Such standards comprise ILO Conventions and Recommendations elaborated and adopted by representatives of governments, employers and workers from all ILO Member States (ILO 2021a). Recognizing that protection outcomes can be attained by various mechanisms, international social security standards set core principles and minimum requirements regarding population coverage, benefit levels, qualifying periods and duration of benefits (see Annex 3), essential rules guiding the financing and administration of social protection systems. International social security standards cover both contributory and non-contributory schemes, in particular social insurance and tax-financed schemes, whether means-tested or not, and, subject to the fulfilment of certain conditions, voluntary schemes. They offer an essential reference framework for policy reforms and implementation, especially the two most prominent instruments in this area: The Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102), provides core principles and minimum benchmarks for social protection systems, across the nine social security contingencies that all people may face during their life: the need for medical care and the need for benefits in the event of:

While not yet universally ratified, this instrument has established the basis for the development of social protection systems throughout the world.1 The Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202),2 provides guidance on how universal social protection can be achieved. This entails the establishment of national social protection floors for all as a matter of priority (horizontal extension), and ensuring higher levels of protection for as many persons as possible, and as soon as possible, by extending coverage to those not yet covered and strengthening national social protection systems (vertical extension). For people to live in dignity throughout their lives, national social protection floors comprise a set of basic social security guarantees that ensure at least:

The relevance of this international normative framework for addressing current challenges is clear. The essential role of social protection has also been highlighted in other recent international labour standards, including the Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy Recommendation, 2015 (No. 204), and the Employment and Decent Work for Peace and Resilience Recommendation, 2017 (No. 205), as well in the ILO Guidelines for a Just Transition Towards Environmentally Sustainable Economies and Societies for All (ILO 2015c; 2023q). 1 To date, Convention No. 102 has been ratified by 66 countries, most recently by Comoros (2022), Côte d’Ivoire (2023), El Salvador (2022), Iraq (2023), Paraguay (2021), Sao Tome and Principe (2024) and Sierra Leone (2022). 2 ILO Recommendations are not open for ratification. |

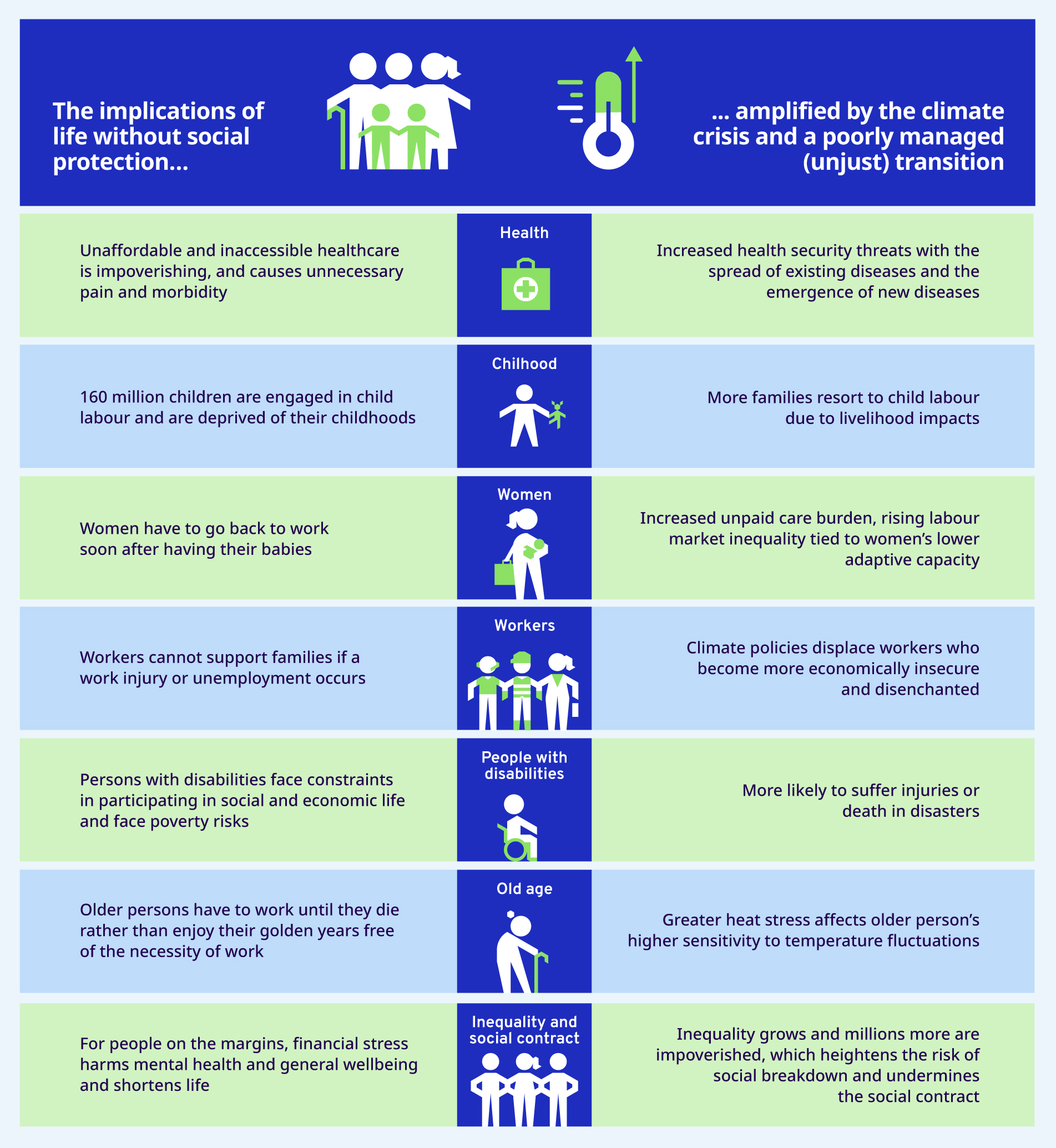

. 1.3 The cost of inaction: The implications of a lack of social protection

Inaction by governments in building and bolstering social protection systems will undermine climate action ambitions and the accomplishment of a just transition. Threatening the stability of entire economies and societies, the climate crisis risks triggering “negative social tipping points” by heightening social tensions, forced displacement, amplified polarization, geopolitical insecurity and financial destabilization (Lenton et al. 2023). Social protection will be critical for holding societies together with each blow dealt by the climate crisis and each phase of a just transition (UNRISD 2022).

Even at the best of times, the costs of inaction by governments are enormous. These costs can take the form of growing inequality, entrenched poverty, labour market informality, squandered development of human potential and capabilities, deep social scarring, public discontent and civil unrest, and lurching from one crisis to the next.

Life without social protection has deep and troubling implications for people (see figure 1.4), and impedes economic development and inclusive climate action. Conversely, it is no coincidence that countries with comprehensive social protection systems enjoy greater prosperity and stability, exhibit higher levels of human development and usually have also greater resilience to climate risks (UNDP 2022). As the previous edition of this report showed (ILO 2021q), the COVID-19 pandemic removed any lingering doubts over the necessity of social protection.

There is ample evidence demonstrating the power of social protection to advance human development and build human capabilities.

As explained above, effective protection against both life-cycle and climate risks strengthens people’s capabilities to successfully navigate the different life phases, transitions and labour market trajectories with confidence and peace of mind. Thus, people can avoid destitution when a shock hits or circumstances change. Ultimately, it allows people to choose lives that are dignified, rational and meaningful. Furthermore, in extreme cases, it can also preserve life by preventing avoidable or premature deaths (WHO 2020) by enabling people to access the basic goods and essential services, including healthcare, needed by all.

At the macro level, social protection functions as a crucial automatic stabilizer and empowers governments to contain and manage crises, and to cope with structural transformations (for example, those provoked by the climate crisis, digitalization and new forms of work) in an orderly and socially fair manner. It delivers substantial “multiplier effects” (Cardoso et al. 2023) and is essential for well-functioning enterprises and general prosperity. Perhaps most striking is its capacity to reduce multidimensional poverty and inequalities, not just by protecting those who already find themselves in poverty, but also by helping to prevent poverty in the first place (ILO 2021q; UNRISD 2022; UNDP 2022; 2023a; Shepherd and Diwakar 2023).

Contending with the climate crisis and the reconfiguration of socio-economic arrangements implied by a just transition seems like a daunting prospect. Universal social protection systems that are adapted to face new challenges will be an indispensable element of the policies needed to contain these risks.

Figure 1.4 What are the implications of life without social protection (selected examples)? What are the cost of inaction?

. 1.4 Building the statistical knowledge base on social protection and monitoring relevant SDGs

This report is based on the ILO World Social Protection Database, the leading global source of in-depth country-level statistics on social protection systems. It includes key indicators for policymakers, officials of international organizations and researchers. It is used for both the United Nations’ SDG monitoring (UN 2023c, 2023d) and national monitoring of social protection indicators. The report’s data and indicators are also available online in the ILO World Social Protection Data Dashboards.2 These dashboards provide a broad set of social protection statistics at the national, regional and global levels through interactive graphs, maps and tables.

Data on the key indicators, including SDG indicator 1.3.1,3 are collected through the ILO Social Security Inquiry, an administrative survey submitted to governments that dates back to the 1940s. In 2020, the ILO launched a Social Security Inquiry online platform, which has improved the data compilation process for users around the world.4 The data from the ILO Social Security Inquiry are complemented by data from other sources, notably the social security country profiles5 compiled by the International Social Security Association (ISSA), which constitute the main source of legal information on national social protection schemes.6

Ever since its first edition in 2010, the World Social Protection Report series has been envisioned as a tool to facilitate the monitoring of the state of social protection in the world (ILO 2010; 2014c; 2017b; 2021q), ensuring the availability of high-quality social protection statistics for national and international stakeholders. It monitors key social protection indicators, such as the extent of both legal and effective coverage and the adequacy of benefits, as well as expenditure and financing indicators, and discusses major challenges in realizing the right to social security for all. Owing to a refined methodology and better data availability, and trend data for the first time, the current global and regional estimates presented here are not necessarily comparable to earlier figures. Yet, substantial knowledge gaps remain, including with regard to adequacy and disaggregation by sex, migration status and ethnicity, which are very relevant to combating inequality.

Progress towards building social protection systems and the achievement of SDG target 1.3, requires enhanced monitoring capacities in order to provide a solid evidence base for policymakers (UN 2023c; 2023d). Indeed, ILO Recommendation No. 202 includes a strong commitment by governments and the social partners to monitor progress, including through participatory mechanisms and according to international standards.7This necessitates systematic investment in national statistical capacities in the area of social protection to make available reliable social security statistics based on a shared methodology and agreed definitions. Additional efforts are thus needed at all levels to strengthen monitoring frameworks and the regular collection, analysis and dissemination of data and statistics on key indicators, disaggregated by function of social protection, as well as by sex, age, migration and disability status, among others.

.1.5 Objective and structure of the report

With only six years remaining until 2030, this report argues that universal social protection will have to be at the heart of climate action and a just transition. It takes stock of the current state of social protection systems, reviews progress made in recent years, identifies remaining gaps and challenges, and sketches out possible pathways for the future.

Chapter 2 focuses on the role of social protection in addressing the climate crisis and facilitating a just transition, and sets out policy options for accomplishing both. Chapter 3 provides an account of core indicators on the current state of social protection. It also argues that, to realize climate ambitions and trigger a just transition, countries need to close current protection gaps, strengthen the institutional and operational capacities of their systems, and adapt them to the emerging challenges of the climate crisis. Chapter 4 closely examines specific areas of social protection, following a life-cycle approach that reflects the four social protection guarantees set out in Recommendation No. 202.8 Section 4.1 focuses on social protection for children. Section 4.2 addresses schemes ensuring income security for people of working age, including maternity protection, unemployment protection and employment injury protection, and disability benefits. Section 4.3 focuses on income security in old age, with a particular emphasis on old-age pensions.9 Section 4.4 addresses the crucial role of universal health coverage for achieving the SDGs. Chapter 5 concludes the report by discussing policy orientations and priorities for the future of social protection, harnessing its key role for achieving the SDGs by 2030, and contributing to climate action, decent work and social justice.

The annexes to this report present a short glossary of key terms used in the report (Annex 1); a description of the methodologies applied (Annex 2); summary tables of the main minimum requirements set out in ILO social security standards (Annex 3) and ratifications (Annex 4); and statistical tables (Annexes 5 and 6, and Annexes 7 and 8 (online only)).